Glasgow has a climate that keeps plasterers on their toes. Rain arrives often, temperatures dip without warning, and indoor air can remain humid for extended periods. Those conditions affect how plaster dries, how it bonds, and how the finished surface looks once decorated. Homeowners usually notice problems after the job seems complete.

A wall that looked fine on day one can develop marks, soft patches, or hairline cracks as the room cycles through damp mornings and colder nights. That is why choosing a plasterer in Glasgow requires more than just finding someone who can apply a smooth coat. Local experience helps prevent failures that appear later.

Why Local Climate Matters

Plaster relies on controlled drying and a stable background. In a damp city, the drying phase can drag on, which changes the strength and finish. Cold air also slows the chemical set, so the surface stays vulnerable for longer.

Indoor conditions matter too. Many properties retain moisture due to older construction, limited ventilation, or daily activities such as cooking and showering. When humid air meets cool walls, water droplets form. That extra water can damage fresh work and cause stains to penetrate the paint.

Slow Curing And Weak Set

Slow curing is one of the most common issues in wet, cool conditions. Plaster needs time to firm up, yet it also needs moisture to leave at a steady pace. When the air is already heavy with water, evaporation slows. The coat can remain soft beneath a dry-looking skin.

That weak set shows up in subtle ways. Trowel marks may not tighten properly. Sanding can tear the surface rather than smooth it. Later, a light knock might leave a dent that would not happen with a properly hardened finish.

Heating can help, but sudden high heat can cause its own trouble. If a radiator blasts one side of a wall while the rest stays cool, uneven drying can create stress. A steady, moderate room temperature is generally safer than rapid changes.

Condensation And Damp Patches

Condensation is a quiet enemy of new plaster. Moist air settles on cooler surfaces, leaving a thin film of water. Fresh plaster can absorb the film, delaying drying and causing patchiness.

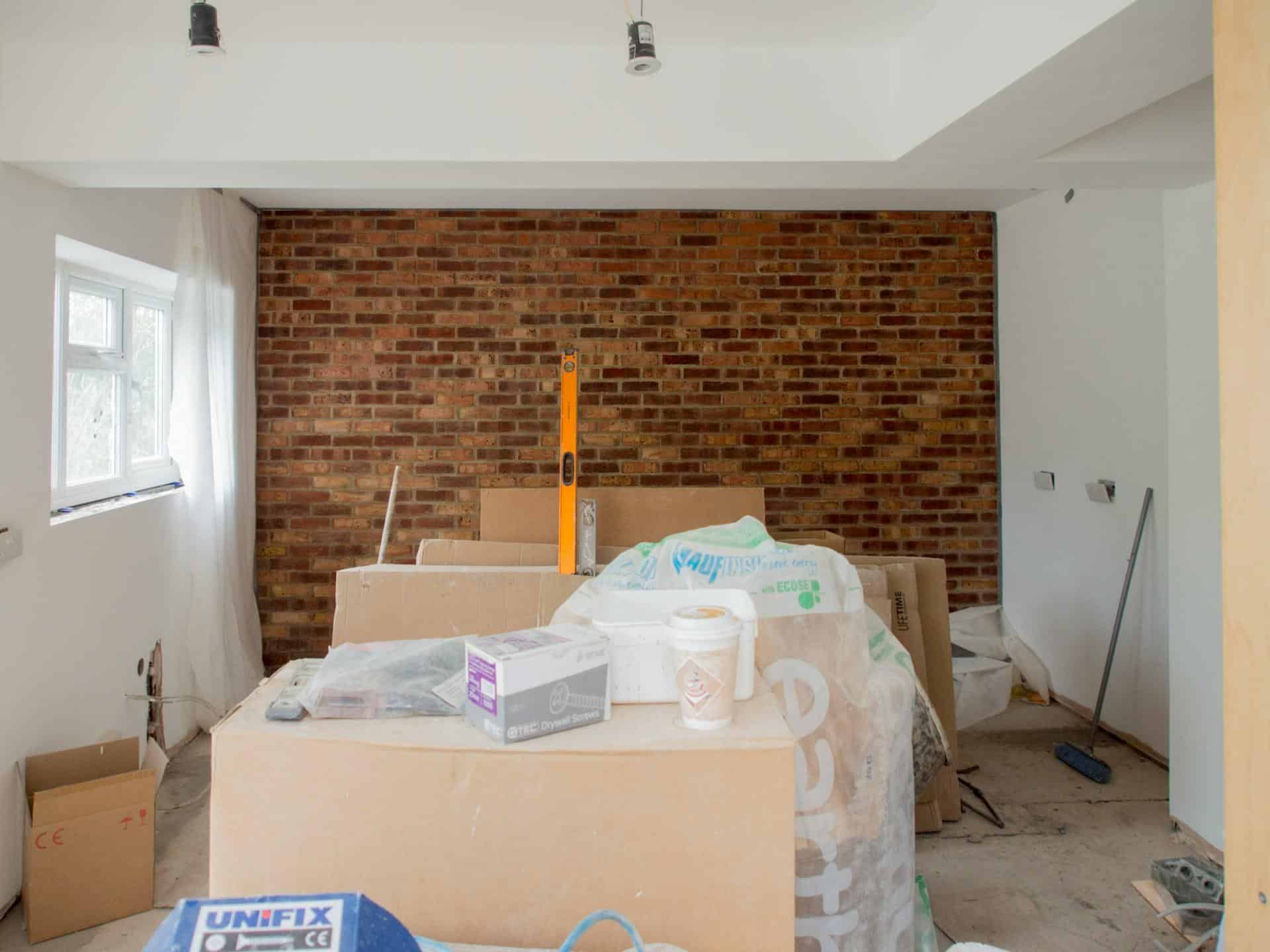

Damp patches also appear when moisture travels from the background. External walls can hold rainwater, especially after storms. Solid masonry and older brick can release water slowly into the new coat. The result is a surface that dries in islands, with darker areas that linger.

Some people try to paint too soon to hide marks. That often traps moisture, which can cause bubbling or peeling later. A better approach is patience, plus sensible airflow, plus checking the cause of the damp rather than masking it.

Cracking, Crazing, And Shrinkage

Cracks are not always a sign of poor workmanship, but weather can increase the likelihood of them occurring. Rapid temperature changes can cause building materials to shift. Timber frames expand and contract. Masonry shifts slightly. Plaster is a rigid finish, so movement can show through as fine lines.

Shrinkage cracks also form when a coat loses water too fast. That can happen near a constant heat source or where draughts focus on a single section. Crazing, which appears as a web of hairlines, may occur if the mix dries unevenly or is overworked during setting.

The background plays a role. If old plaster is dusty or unstable, new material may not grip properly. Small cracks can then spread along weak spots. Proper preparation, including cleaning and priming when needed, reduces that risk.

Blistering, Flaking, And Delamination

Surface failure often stems from moisture and poor bonding. Blistering happens when trapped water or air pushes up under a finish layer. Flaking can follow if the top coat loses adhesion. Delamination is more serious. A section can sound hollow when tapped, showing that the coat has separated from the wall. This can occur if the substrate was too damp, too smooth, or contaminated with old paint, grease, or salts. Cold conditions can also shorten working time, leading to rushed applications on a background that is not ready.

Bathrooms, kitchens, and utility rooms are common trouble spots. Steam and poor extraction add moisture. If the base is not sealed correctly, water movement can undermine the plaster from behind.

Salts, Staining, And Patchiness

Glasgow properties often have older walls that have absorbed moisture over the years. When water moves through masonry, it carries salts. As the water reaches the plaster surface, salts can crystallise, leaving white marks or brown stains.

Patchiness can also come from uneven suction. Some areas of a wall pull water quickly, while others stay slow. That difference affects how the plaster sets and how it dries. Even after decorating, the finish may look mottled under certain light.

Stains should not be ignored. They can indicate a leak, bridging from an external defect, or rising damp. Treating the symptom without addressing the root cause usually leads to recurring problems.

Practical Steps And When To Call Help

The weather cannot be controlled, yet the risks can be managed. Ventilation is important, but strong drafts can cause uneven drying. Gentle airflow is better than a window left wide open during a wet spell. Stable heating helps, keeping the room warm without extreme temperature swings.

Preparation is where expertise shows. A skilled plasterer checks the substrate, addresses loose material, controls suction, and selects the appropriate system for the room. Some walls need bonding, some need a different base, and some require addressing dampness first.

Timing is another factor. External repairs and internal work on cold outer walls are more difficult during prolonged wet periods. Planning around the worst conditions can reduce complications. When problems arise, early intervention can prevent a minor defect from becoming full reskin.

A Finish That Stays Sound

Glasgow’s weather adds pressure to plastering, as moisture and temperature affect every stage of the job. Slow curing, condensation marks, cracking, and surface failure often come from the same root cause: the environment and the wall were not treated as part of the process. With careful preparation, appropriate drying conditions, and experienced hands, plaster can still cure evenly and maintain a clean, lasting finish.